The arrival of hunters

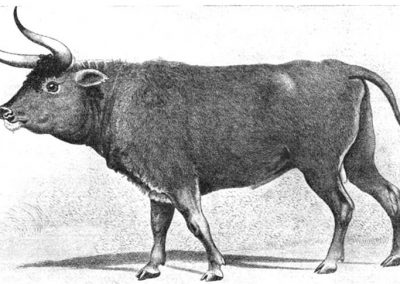

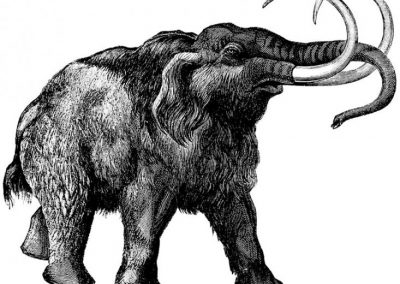

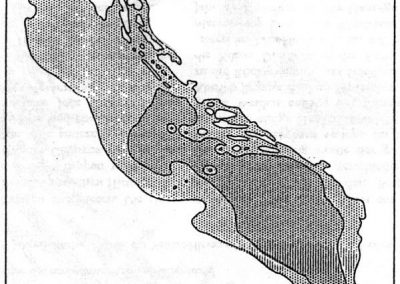

At the peak of the Ice Age, some 16,000 years ago, a large part of the water that makes up today’s seas was captured in the ice caps that covered vast areas of the Earth’s northern hemisphere. At that time, the sea-level was as much as 120 metres lower than today: the Adriatic was just a gulf that ended somewhere around today’s town of Zadar in Dalmatia, and its present northern part was a spacious steppe, a rich hunting area inhabited my many beasts that are today extinct, like the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, aurochs and European bison. Today’s coastal mountains, like Učka, were at the time several hundred kilometres from the sea, and covered with thick pine forests. Their peaks were often wrapped in a permanent covering of ice. As such, these mountains did not represent particularly interesting habitats for the small human communities of hunter-gatherers.

Then, some 13,000 years ago, this situation started changing quickly – rapid warming marked the end of the Ice Age, ice started withdrawing from the European continent, and water began filling the former wide steppes. This change was very dramatic for the people of that time – the Adriatic coastline could move several kilometres during a lifetime!

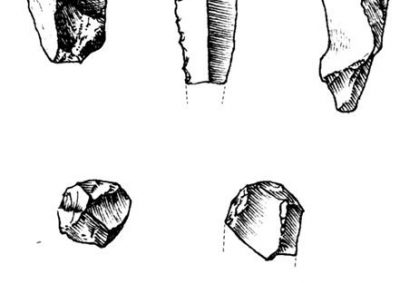

Driven back by the incoming water and encouraged by the warming that made the mountains more accessible, small groups of people began inhabiting the Učka area and using it as a seasonal hunting ground and home. The Pupićina peć and Vela peć cave complex in Vela draga is one of the most important Croatian archaeological sites from that period. Certain items dating back 12,000 years confirm that a small community of people, consisting of only a few dozen individuals, would come to these caves mostly in the autumn to hunt deer, wild boars and aurochs.

The beginnings of environmental management

Global warming and environmental changes were followed by changes in the human way of life. In that period, conditions emerged that made survival possible regardless of the favour of nature or hunting success. Some 10,000 years ago, human communities in the Middle East domesticated some of the animals they previously had hunted, such as wild sheep and goats, and soon after that began growing their own crops, thus ensuring for the first time their own source of food. This was the beginning of the Neolithic or New Stone Age.

It took several thousand years more to extend these new practices to the northern Adriatic area – a time when the sea for the most part had reached its dimensions as we know them today. However, the first cattle-breeders that came here found quite a different landscape. The first thing they had to do was to clear the dense mountain forests to create pastures for their herds. This is how the first, wide mountain pastures came into being, such as the valley of Gospin dol and Sapaćica. These pastures are today recognisable landmarks of the mountains of Učka and Ćićarija. This was the beginning of the cattle-breeding way of life that has continued right up to the present day.

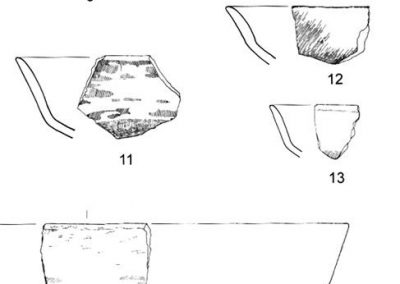

At first, sheep and goats were raised primarily for meat. However, ceramics and bones found in the Neolithic layer of the cave of Pupićina peć indicate that local shepherds soon mastered the techniques of milk processing. A large number of ceramic vessels that were used for milking, and the disproportionately large number of bones of young animals that had been eaten, indicate that people tried to preserve as much milk as possible for consumption and processing.

These shepherds pursued a partly nomadic way of life that has survived among sheep breeders right up to the present day: depending on the season and grazing conditions, they would migrate with their herds between established pastures at various sites and elevations above sea-level. Only the later arrival of the first agricultural cultures into this area created the conditions for establishing permanent settlements that resembled our present-day villages.

The Bronze Age – a period of flourishing and turmoil

The discovery of metals contributed to the flourishing of trade, but also led to the growing military power of human communities. This period marked the arrival of the first conquerors, the first local kingdoms and tribal alliances.

The next major innovation in the human way of life and the managing of resources was the discovery of metals – copper at first, and shortly afterwards its tin alloy, bronze. Due to their hardness and ductility, metals facilitated the development of various new tools and weapons, which led to the further development of agriculture, but also to the strengthening of military power. The production of bronze encouraged the development of trade throughout the Europe of that time: the metals that make up this alloy, tin and copper, are very rarely found in the same spot, which means obtaining these materials requires trading with distant regions.

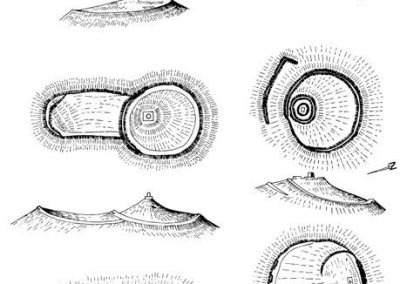

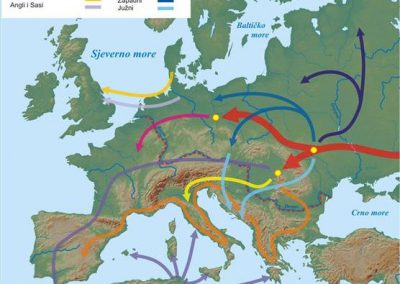

Due to the invention of the plough and the overall progress of farming, agricultural societies started producing surplus food, sufficient for those in the population that were not engaged in its production, such as the warriors, rulers or clergy. Such cultures spread and migrated at the cost of less-developed indigenous populations, resulting in the arrival to Istria and Liburnia of the Indo-European ethnic group, which today makes up the majority of Europe’s population. With the arrival of these newcomers, the former simple human communities gave way to the first local kingdoms and tribal alliances that left their mark on the landscape of Učka and Ćićarija by building many hill forts that were used to control trade routes or as refuges during the frequent periods of war.

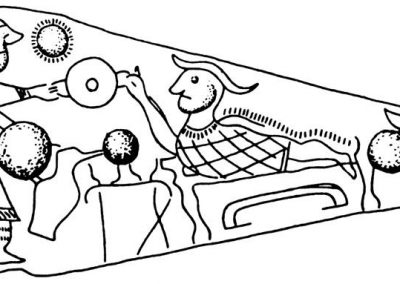

Most prominent among the newcomers were the Illyrian peoples of the Histrians and the Liburnians, whose territories were demarcated by the ridge of Mount Učka. Despite the fact that they never developed literacy and high culture, these peoples lived at the margin of the ancient world thanks to trade with the Greeks and Etruscans, and adopted many of the aesthetic characteristics and customs of their more developed neighbouring cultures.

Pax Romana and the period of abundance

After the Roman conquest, Istria and Liburnia entered the period of written history. Roads were built over the mountain passes, and the increasing demand for food from the newly built towns and the large army required a more intensive type of cattle-breeding and agriculture.

After taking over the whole Apennine peninsula in the 3rd century BC, the Roman Republic continued spreading all the way to the borders of the Histrian kingdom. It wasn’t long before this small neighbour, which stood in the way of expansion to the east, became the target of further conquest. In 177 BC, under the pretext of Histrian piracy, Roman legions surrounded the Histrian capital, Nesactium, and conquered it after a siege that resulted in the suicide of the Histrian king Epulon. Soon after that, the provinces of the neighbouring region of Liburnia also became part of the Roman Republic, which means that the whole area around Učka and Ćićarija now became officially part of the ancient world and its written history. In the long period of peace that followed, many Illyrian towns became Roman urban centres, and some new settlements were also established.

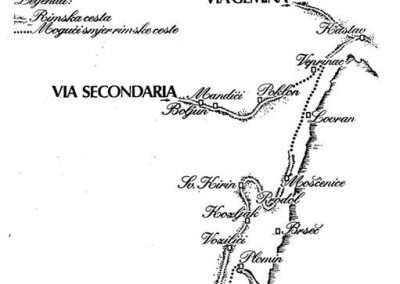

The Roman conquest had only an indirect effect on Učka and Ćićarija for the most part. There are no significant traces of Roman architecture on the mountain itself; however, to connect Italy with the eastern provinces, two roads were built over it: the Via Flavia, which connected Pula and Tarsatica over the Prodol pass above Kožljak, and the Via Secondaria, which connected Liburnia with the towns in Italy over the Poklon pass.

The rapid growth of urban centres throughout the Roman Empire, as well as the demand for food from the vast military apparatus, encouraged a more effective agricultural use of land. Archaeological finds from the caves of Učka and Ćićarija attest to extensive sheep-farming activities in this area, and traces in the erosion layers indicate a large expansion of pasture and agricultural areas during that period.

One specific heritage of the Roman times are the two cheeses known as učkarski sir and ćički sir, whose present recipe does not vary much from the Roman records that describe production of this hard cheese. The production of this cheese, called Caseus formatum (literally “moulded cheese”), was standardised because it formed part of the Roman legions’ daily ration. Following the Roman conquests, this cheese started being produced in many parts of the Mediterranean and Europe, where it later adopted some local features. This led to the creation of a variety of famous European cheeses that we still know today – among them the cheeses locally known as “učkarski sir” and “ćički sir”.

The Middle Ages

After losing the protection that coastal areas enjoyed under the Roman state, the mountain again becomes a place of refuge and safety. Migration changes the ethnic composition of this area and brings in the ancestors of the present Croats.

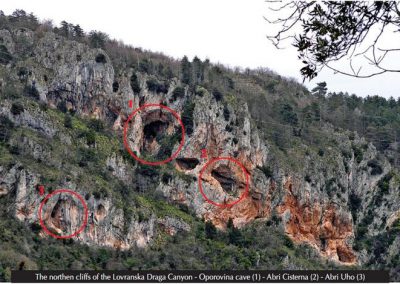

In the 5th century AD, the period of peace secured by the Roman Empire finally drew to an end. The decline of the empire was followed by a series of barbarian invasions and devastation, which made life along the coast so unsafe that local people moved up into the mountains. This was a time when ancient sites, such as the Oporovina complex of caves above Medveja, were settled anew as places of refuge. Forts and refuges were built, and small fortified urban centres emerged which would eventually become medieval communes, such as Brseč, Mošćenice, Lovran and Veprinac.

Perhaps the most important event in the Early Middle Ages for this area was the arrival of Slavic tribes in the final years of the Migration Period. An important reminder of that era is the sacred area of the old Slavic religion in the hinterland of Mošćenice, between the hamlet of Trebišća and Mount Perun. Local toponomy is imbued with terms from the Old Slavic myths, indicating that the first Slavic settlers on Kvarner gave this landscape a sacred relevance.

In the 10th century, Učka was the border between the Croatian Kingdom and the Frankish Empire, and later in history, this area became the subject of struggles and demarcation among many states and the changing feudal rulers of the Istrian and Liburnian territory. A series of fortifications and castles remind of that period. These were mainly built in strategic locations that had previously been used as hill forts. The most prominent example within Učka Nature Park is the fort of Kožljak, built around the 11th century by Frankish vassals.

At the end of the Middle Ages, in the 15th century, some of the mountainous parts of Istria that had previously been devastated by plague became inhabited by Vlach people who would later become known as Ćići or Istrian Romanians. By bringing their own specific language and sheep-farming tradition, they made a significant contribution to the development of the local culture and way of life.

Tradition

The traditional life and economy of Učka and Ćićarija are the result of a millennia-long coexistence with the local landscape, and the cultural contributions of all the peoples and communities that once lived here.

In the period that followed the Middle Ages to the modern era, the traditional culture and way of life on Učka and Ćićarija assumed their final form. Potato and corn, two vegetables that would play an important role in the agriculture on the mountain and the diet of local people, were brought here from the Americas. Travel writers who visited this area, like Johann Weikhard Valvasor, wrote that on the slopes of Mount Učka “lie many vineyards, and their grapes are full of good wine“. He also described the local people as follows: “many of them make a living from other fruits, such as large, sweet chestnuts that are exported to distant lands, since here grow entire forests of these chestnuts“.

This was the time of greatest population density and utilisation of Učka and Ćićarija. Villages had up to 600 inhabitants and were characterised by vibrant economic activity. To meet the needs of the people who lived in the valleys, on the coast and in the nearby towns, people on the mountains produced and exported cheese and charcoal, and gathered fruits of the forest. Since the men were working all day long in the fields and pastures, the merchandise was often carried by local women on the back to the market places in Liburnia and Istria.

Today, the cultivated landscape with terraced gardens, karst valleys and pastures, as well as the rich architectural heritage, recall these times and way of life, attesting to the millennia-long tradition of life in this area. Because of their original ambience and architecture, particularly interesting settlements within Učka Nature Park are the villages of Lovranska Draga, Mala Učka, Brest pod Učkom and Brgudac. Among the small abandoned hamlets, one should not forget to mention Trebišća, Petrebišća and Podmaj. Important parts of the local heritage too are the ancient roads and water supply systems, built by the former Austro-Hungarian administration for the needs of local people and travellers, such as the Water of Joseph II fountain, or the Korita source area.

Pictures: hinterland of Lovran, Ćićarija, Korita (troughs), traditional activities, and shepherd’s huts.

19th and 20th centuries

The development of tourism and mountaineering brings the first visitors and facilities to Učka.

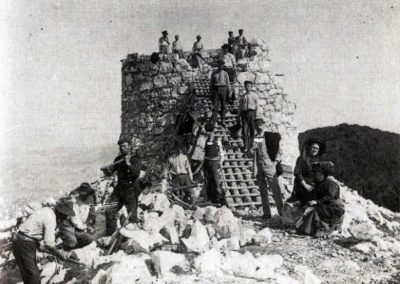

In the second half of the 19th century, the development of transport and civil society within the Austro-Hungarian Empire resulted in the first significant changes in how people from the surrounding areas looked at Učka and Ćićarija. The fact that Opatija and Lovran were proclaimed climatic health resorts was also due to the climatic influence and the beauty of the area’s mountainous hinterland. It didn’t take long before tourism started spreading from the coast into the mountains. A report from the first documented ascent of Učka’s highest peak, Vojak, was published in 1852 in Zagreb’s Neven magazine under the title Dawn at Učka. One of the first mountaineering organisations in this part of Europe, the Club Alpino Fiumano, was founded in 1885. In 1887, the Crown Princess Stephanie Mountain Hut was built on the Poklon pass, and the first official trail to the peak of Vojak was marked out. In 1911, members of the Austrian Tourist Club finished constructing the stone tower at Vojak. Local people at first looked with distrust at their visitors from the town and their unusual interest in climbing the mountain for no particular reason. However, they soon realised that these visitors, who needed refreshment and accommodation, are a valuable source of income.

During World War Two, the area of Učka and Ćićarija was the centre of guerrilla resistance to the occupying forces. This is particularly true of the village of Brgudac, which today hosts a memorial centre dedicated to the people’s struggle against fascism. Almost all the villages on Učka and Ćićarija have a memorial plate or monument recalling the terror wrought by the German army in the spring of 1944, during its last desperate attempts to break the resistance of the local people.

Pictures: old tourist and hiking photographs, memorial plaques

The mountain and the modern world

The change in socio-economic conditions resulted in the disappearance of traditional activities on Učka and Ćićarija. But the beginning of the 21st century marked a reawakening of interest in the local culture and way of life, bringing new hope for their survival.

Apart from the ravages of World War Two, the most important factor in the disappearance of rural life on Učka and Ćićarija in the 20th century was the change of social and economic circumstances, resulting in more and more people abandoning their traditional ways and moving to the towns. Many beautiful rural houses and most of the shepherds’ huts are today only ruins. This change did not affect only human communities and culture: pastures, on which today only a few sheep graze compared with the past, are being rapidly overgrown by thicket and macchia. This is resulting in the loss of habitats for many important plant and animal species, and the disappearance of a valuable example of peaceful human coexistence with nature.

However, today, after the end of the century in which this process began, we can notice a renewal of interest in the traditional culture and way of life, and in authentic, healthier ecological products. This is probably a reaction to the fast-paced modern world of mass production and consumption, and is best reflected in the increasing interest in events aimed at promoting traditional values such as the Učka Fair. These values represent a foundation for the development of sustainable tourism in this area: modern visitors appreciate authentic original culture that reflects its roots and origins.

This traditional way of life has not yet been entirely lost – some sheep still graze on the pastures of Učka and Ćićarija, and some households still produce cheese. Old stories, local customs, and even the traditional plant and animal species that used to be cultivated here, are today being collected and preserved thanks to the efforts of local people and experts. The fact that there is a wide interest and awareness about the need to preserve cultural roots and achieve sustainable coexistence with nature in our society gives hope that we will be able to preserve these values and restore the meaning and dignity of the culture and way of life from which they emerged.

Pictures: ruined villages, Mira and Massimo, Učka Fair